|

| Picture #1: View of Anderson Stream at Lake Hoare. |

Now that you have some background on the Dry Valleys, I

thought I would take a little time to talk about my experiment. I’m seeking to

determine both the amount and chemical composition of suspended sediments in

glacier-fed streams. In case you’re wondering what I mean by suspended

sediments, it refers to the particulate (= not-dissolved) material that can be

carried by a stream. This is the material that can often give streams a

brownish color during storms. There is little to no data on suspended sediment

loads and chemistry of Dry Valley streams, so I am excited to contribute

something new to our knowledge of these systems.

While glaciers may look like pure compressed snow and ice in appearance they actually carry a substantial amount of sediment. In the case of these Taylor Valley glaciers, much of this material likely originates from windblown dust within the valley along with some potential contributions of ash from Mt. Erebus, a nearby volcano. However, it is unclear as to whether these are the only two sources of sediment.

|

| Picture #2: View of VanGuerard Stream at F6 |

|

| Picture #3: View of gauge located along Anderson Stream. |

In order to get a better handle on how suspended concentrations may change over time I designed my study into three parts: (1) periodic sampling of rivers throughout Taylor Valley, (2) daily sampling of two streams of interest (Anderson Stream at Lake Hoare and Van Guerrard at F6), and (3) diurnal (24 hour) sampling of these two streams of interest (Pictures 1 &2). Like many scientific studies, this one definitely requires cooperation. Samples for the first part of the study are collected by a group known as the “stream team.” This is a rugged bunch of individuals who often hike to several locations in one day in these valleys to collect samples (Lucky for me they agreed to collect additional samples for my study). Samples for the second part the study, the daily sampling, are collected by the respective camp managers for Lake Hoare and F6 (Again, I’m indebted to their generosity). It’s the third part of the study that fully occupies my time in the field due the intensive time required.

For diurnal sampling, you’re basically trying to understand

how a system, in this case a stream, operates during the course of a day. While it doesn’t necessarily matter when you

begin sampling, it does require you to sample frequently over a 24 hour

period.

|

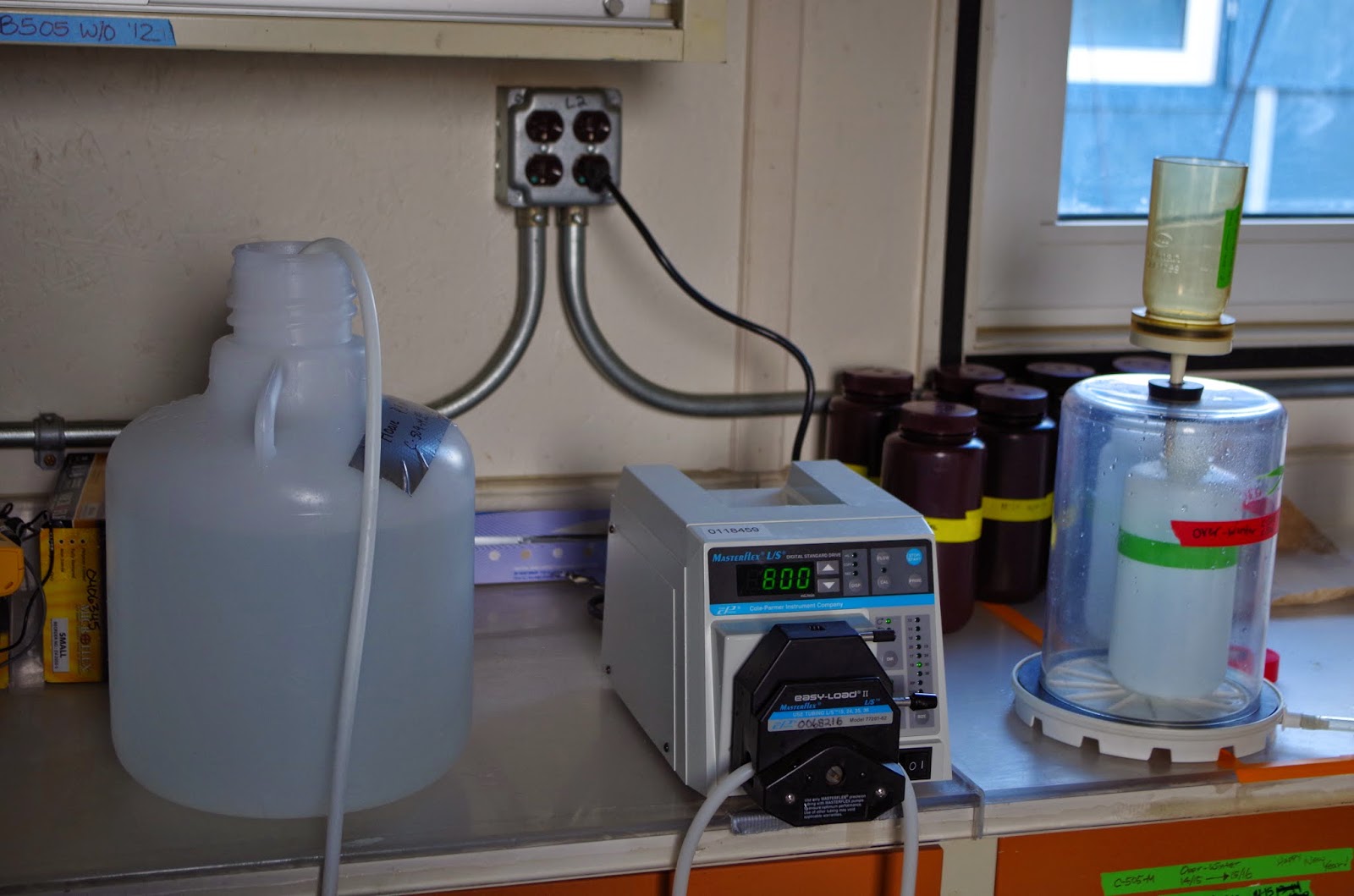

| Picture #4: View of filtering equipment in the mini-lab at Lake Hoare. |

In order to have some idea as to how much suspended sediment

might be moving down a stream, you need to know the concentration of sediment

in the water as well as how much water is moving down the stream at any given

time. For the latter, I purposefully chose locations where stream gauges, or

devices used to record stream flow are already located (Picture 3). Therefore, my job is to collect water samples

by hand at each sample interval to determine sediment concentration. One catch is that in order to retrieve enough

suspended sediment to analyze for its chemistry I need to collect 10 liters of

water (Picture 4). That’s basically the equivalent of 2 1/2 gallons of water!

To date, I finished one diurnal sampling of Anderson Stream,

which is loc

ated adjacent to the west side of Canada Glacier. Although the sun shines all day at this point

in the year, its relative height and position change throughout the course of a

day. The unique conditions for this area

of the valley cause a peak in streamflow around 4pm and another one around

11pm. The lowest flows are recorded in the morning. Therefore, I spread my sampling

intervals out during the morning low-flow period. However, from 4pm to 4am I

collected samples every hour. I

subsequently brought these samples to the small lab shed where I’ve been

patiently filtering ever since! |

Picture #5: View of the drainage patterns in Canada Glacier

illuminated by the nighttime sun.

|

The one really neat thing about staying up so late to sample

is that you get to see the sun hit the landscape in unique ways. Views that

seemed ordinary at first suddenly appeared unworldly. In some cases, this different illumination of

the landscape yielded very important information, such as the appearance of

what looked like tiny streams with tributaries draining Canada glacier! (Picture #5) Overall,

it gave me the distinct feeling that I was working on an alien planet.